The Human Condition, The Human Dimension

- Albert Durig

- Aug 18, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Aug 21, 2025

For the sake of establishing a shared meaning, I propose a distinction: the human condition is always bound to context, while the human dimension is not. By “human condition,” I mean the fundamental traits, experiences, and challenges inherent to being human as they are lived within the context of current social structures and norms.

These include universal aspects of existence—learning, emotion, aspiration, morality, conflict, suffering, and the search for meaning—but always as they are shaped by the world we inhabit at a given moment. The human condition is not static; it shifts with history, technology, economics, and politics. In the present moment, our human condition is profoundly marked by the realities of our technological, economic, and geopolitical landscape. It is defined by unprecedented access to information, the proliferation of online echo chambers, polarized politics, divisions across religion, race, and gender, new modes of consumption, and evolving approaches to health and life itself. It is a condition that embodies both the extraordinary promise of freedom and innovation and the persistent presence of fear, inequality, and unrest. For many, this condition feels unsettled, unfulfilling, or at the very least deeply uncertain.

When we ask why we feel this sense of dissatisfaction or disorientation, our attention usually turns to familiar sources—our relationships, health, work, family, or daily routines. These are important factors, but they are not the whole picture. What we often fail to recognize is the profound influence of our place in history. It may feel strange, even melodramatic, to connect our private struggles to vast historical or sociological forces. Yet our individual lives are never divorced from the larger currents of our age. To fully grasp our present sense of unease, we must acknowledge that it is bound up with the unique and unprecedented context we are living through—a moment of rapid technological acceleration, shifting values, and profound redefinition of what it means to be human.

Today’s human condition is deeply shaped by an imbalance in how we see ourselves and the world around us. The School of Life, in its essay “How History Can Explain Our Unhappiness,” captures this tension with striking clarity:

“At the center of all premodern societies were powers that helped to put humans in their place; older, bigger, stronger, holier phenomena—perhaps a god, natural energy, or a spirit. However important humans might have felt, however grand the aristocracy or urgent the news of the day, people knew that they were not the measure of all things. The fanciest king was nothing next to a thunderous god; the mightiest invention pathetic next to an angry sea. But we humans are now the most astonishing things we can conceive of: it’s our momentous doings, our intelligence, our incomprehensibly wondrous technologies that mesmerize us and are at the center of collective consciousness.”

What this passage reveals is a profound shift in human orientation. Where once we were humbled by forces beyond ourselves—divine, natural, or cosmic—we now place ourselves, and especially our technologies, at the very center of reality. The thunderous sea has been replaced by the thunder of our inventions. The holy has been overshadowed by the marvel of human-made intelligence. This reorientation, while empowering, is not without cost. It alters how we think about our work, our place in society, and the sources of meaning in our lives.

In earlier centuries, work often culminated in something tangible. A farmer could point to their harvest, a carpenter to their chair, a potter to a vase, a mason to a barn. Labor was visibly and physically tied to creation. The meaning of one’s work could be located in the object itself, in its permanence and utility. Today, however, much of our work is abstract, fragmented, and digitally mediated. We move information, manage processes, and interact with data flows rather than shaping material goods. Tasks are divided, outcomes are dispersed, and the connection between effort and result is often obscured. The result may be efficiency and wealth on a massive scale, but it often comes at the expense of clarity, meaning, and fulfillment. Many workers feel as if they are cogs in a vast machine—necessary but interchangeable, productive but disconnected from a sense of contribution.

This alienation is not incidental. It is a product of how humans have always adapted to changing social and technological landscapes. Each new era reconfigures the human condition. The Industrial Revolution brought its own forms of alienation, as workers left agrarian life for factories, trading the wholeness of craftsmanship for the repetition of industrial labor. The digital revolution has taken this further, dissolving the tangible product altogether into flows of data and screens of numbers. The meaning of work, once embodied in what was made, is now abstracted into outcomes we often cannot see or touch.

THE HUMAN DIMENSION

The “human condition,” then, is not simply a timeless set of traits. It is the lived response of humanity to the shifting structures of history. It evolves with us, shaped by the context we inhabit and the choices we make. To call our current condition unsettled or unfulfilling is to recognize that our responses to technology, politics, and culture have created a state in which many feel disconnected from meaning. But this too is part of a cycle: as contexts change, so too do our responses, our beliefs, and our search for purpose.

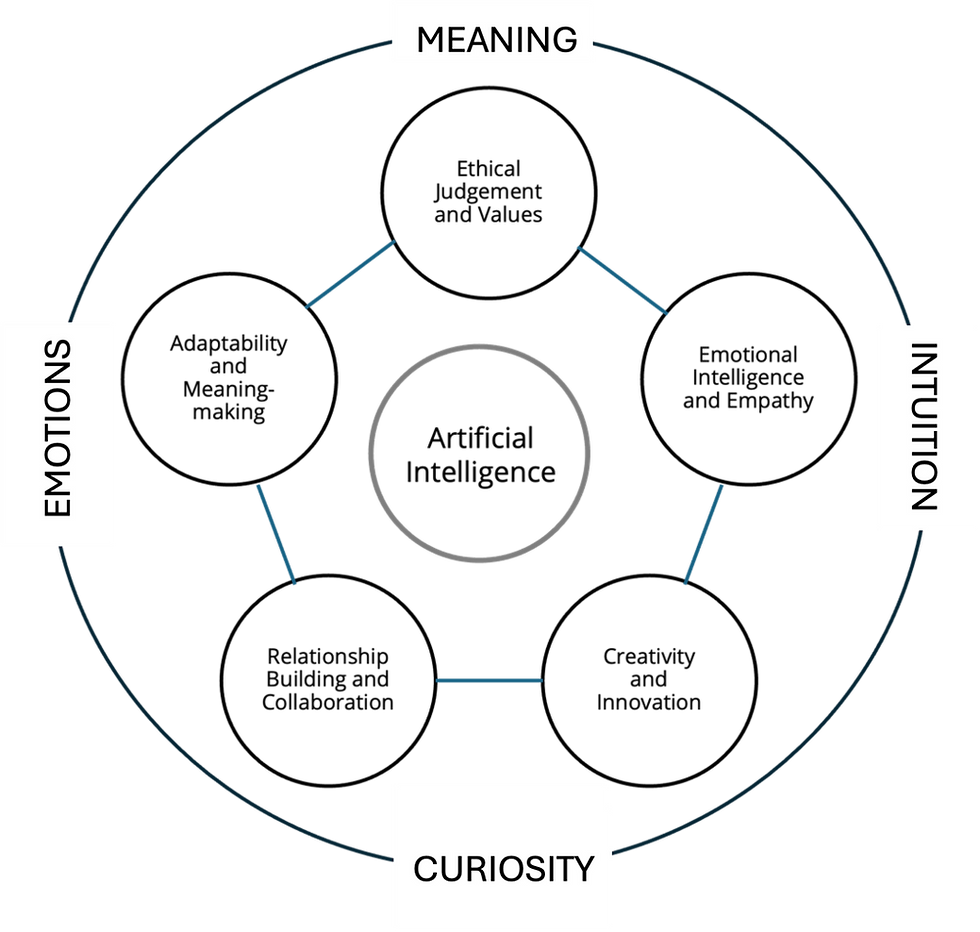

That is why it is crucial to differentiate the human condition from the human dimension. The condition reflects the context-bound realities of living in a specific era; the dimension reflects the enduring capacities and values of being human beyond context. In other words, while the human condition shifts with history, the human dimension offers a more stable foundation—our inherent potential for connection, empathy, creativity, and moral reasoning. Together, these categories help us better navigate the challenges of our time.

By placing ourselves and our technologies at the center of reality, we have created both immense power and immense imbalance. The very tools that expand our reach also unsettle our sense of meaning. This paradox is the defining challenge of today’s human condition. And it is why, if we are to thrive in the age of AI, we must not only analyze the technical changes that shape our daily lives but also confront the deeper ontological questions of who we are, what we value, and how we will choose to live.

What Does It Mean To Be Human?

The question of what it means to be human has echoed through philosophy, science, religion, and art for millennia. Each era has asked it anew, reshaped by the context of its time. There may never be a single definition that captures the full depth of our humanity, but there are recurring themes that continue to illuminate the contours of the human experience.

One of the most defining elements of being human is consciousness and self-awareness. Unlike other beings we know, humans possess the remarkable ability to reflect on their own existence. We do not simply act; we consider why we act. We wonder about our purpose, weigh our morality, and wrestle with our identity. Consciousness allows us not only to experience life but to interpret it, to assign meaning to our emotions and choices, and to imagine futures not yet lived.

Closely linked to this is our capacity for reasoning and intelligence. Humans engage in abstract thought, problem-solving, and creative innovation at scales unparalleled in the natural world. It is this ability that has propelled us to build civilizations, design technologies, write literature, and adapt to every environment on Earth. Reasoning enables us to solve problems in the moment, but also to envision solutions to problems that do not yet exist—a uniquely human ability to project possibility into the future.

Hand in hand with thought comes language and communication. Language allows us to convey complex ideas, pass down knowledge across generations, and create shared understandings that bind communities together. More than just a tool for survival, language is the medium through which culture, science, and history are preserved and expanded. It is a symbol system that enables us to collaborate, tell stories, and articulate values that extend beyond any single individual’s experience.

Yet to be human is not simply to think and to speak—it is also to feel. Our emotions and empathy shape the richness of our lives and the bonds we share with others. Emotions ground us in meaning, while empathy allows us to step outside ourselves and imagine the world from another’s perspective. These capacities are not peripheral but central to our survival and flourishing. They underlie our ability to cooperate, to care, and to form trust—the very glue of social life.

Humans also participate in culture and symbolism. We create art, music, religion, traditions, and rituals that give shape to our collective imagination. Culture is not an accessory to life but a framework that defines who we are, what we value, and how we interpret our place in the world. Through symbolism, we build bridges between the material and the transcendent, between what is and what could be.

From this emerges our tendency to form socio-emotional bonds. Humans are deeply relational beings, wired for belonging, support, and resilience. We thrive not in isolation but in communities, families, and networks of meaning. It is in connection with others that we discover ourselves and find strength to endure hardship.

Finally, to be human is to live with moral and ethical awareness. We carry within us a sense—shaped by culture, conscience, and experience—of what is right and wrong. This awareness influences not only our personal decisions but also the systems of law, governance, and cooperation that make collective life possible. Morality binds us to responsibilities beyond ourselves and challenges us to act in ways that sustain justice, fairness, and dignity.

Taken together, these threads—consciousness, intelligence, language, emotion, culture, relationships, and morality—form a fabric that is uniquely human. To be human is to live within this rich weave of thought, feeling, meaning, and connection. Our identity is not defined by biology alone, nor intellect in isolation, but by the interplay of our choices, relationships, and the historical moment we inhabit.

What Does It Mean To Be Artificially Intelligent?

If we ask what it means to be human, it is only fair to also ask what it means to be artificially intelligent. The very existence of AI challenges us to define intelligence anew, to distinguish between what arises naturally through biology and what is constructed through algorithms and machines. Just as with humanity, no single definition captures the full range of artificial intelligence, but certain descriptions from respected sources give us a starting point.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines Artificial Intelligence as “the capacity of computers or other machines to exhibit or simulate intelligent behaviour.”

Merriam-Webster Dictionary describes it as “the capability of computer systems or algorithms to imitate intelligent human behavior.”

Britannica states: “Artificial Intelligence (AI), is the ability of a digital computer or computer-controlled robot to perform tasks commonly associated with intelligent beings.”

Wikipedia summarizes AI as “the capability of computational systems to perform tasks typically associated with human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, problem-solving, perception, and decision-making.”

And ChatGPT itself defines AI as “the field of computer science focused on creating systems or machines that can perform tasks that typically require human intelligence—such as learning, reasoning, problem-solving, understanding language, and recognizing patterns.”

Despite their variations, these definitions converge around a set of common themes.

It’s Artificial, Not Natural

First, AI is artificial, not natural. Its intelligence does not emerge from evolution, biology, or lived awareness but is engineered through algorithms, data, and code. It is a simulation of intelligence, not an expression of life itself.

It’s Intelligence as Function, Not Experience

Second, AI embodies intelligence as function, not experience. It processes data, identifies patterns, learns from inputs, and makes decisions, but it does not experience consciousness, self-awareness, or emotion. Where humans understand, AI computes. Where humans feel, AI simulates. This distinction is critical: intelligence in machines is about execution, not meaning.

It’s Mimicking Human-Like Abilities

Third, AI is fundamentally about mimicking human-like abilities. It can analyze massive datasets, predict outcomes, recognize images and speech, generate language, and even adapt to new circumstances without explicit reprogramming. In many cases, it performs these functions with greater speed, scale, and precision than humans. Yet behind this competence lies no intent, no desire, no awareness. It can hold a conversation but does not know it is speaking. It can replicate logic without grasping meaning. It can map probability but not purpose.

And perhaps just as important as what AI can do is what it cannot. It cannot create from lived experience, nor does it carry intrinsic values. It does not grapple with mortality, nor does it feel the joy or sorrow of relationships. It can assist in decision-making but does not shoulder responsibility. It can mimic empathy but cannot truly care. In this sense, AI’s limits are as revealing as its capacities.

Humans, Machines, and the Question of Value

When we set the definitions of human and artificial intelligence side by side, the contrast is striking. Humans live in a world of meaning, relationships, and moral responsibility. AI operates in a realm of data, algorithms, and function. Humans carry consciousness, awareness, and emotion. AI carries processing power, scale, and speed.

The pressing question, then, is not simply what AI can do, but how humans can add value in a workplace increasingly surrounded by machines that are intellectually more capable in narrow functions. The answer, I believe, lies in reclaiming and amplifying what is distinctly human: our empathy, our moral judgment, our creativity rooted in lived experience, and our capacity for trust and relationship-building.

AI may compute faster, but it cannot feel. It may simulate conversation, but it does not understand meaning. It may generate text, images, or strategies, but it does not create out of love, longing, or aspiration. These uniquely human dimensions are not only irreplaceable—they will become more essential as technology advances. The workplace of the future will not be defined by a competition between human and machine intelligence, but by the quality of collaboration between them.

Human Work

What exactly do we mean when we talk about human work? At first glance, one might assume it refers to any task performed by people. Yet, if that were the definition, much of what we call human work could just as easily be carried out by machines or delegated to artificial intelligence. So the more important and pressing question is not what work do humans perform? but rather, what makes work human?

This distinction has been explored in depth by Jamie Merisotis in his book Human Work in the Age of Smart Machines. Merisotis recounts his conversation with Katie Albright, the CEO of Safe & Sound, a San Francisco–based organization devoted to preventing child abuse and reducing its devastating impact. What stood out to him was not only what Albright’s organization does, but how she speaks about the work and the people involved. Her language, as Merisotis observes, reveals the essence of human work.

Albright describes Safe & Sound’s mission with a deep compassion for the people it serves and a profound respect for the staff who support them. She embodies the qualities at the very center of human work: empathy, ethical clarity, and communication grounded in listening. Merisotis notes that she consistently evaluates what is effective and what is not, demonstrating a commitment to critical judgment and adaptation. Her ethical focus guides decision-making, while her capacity for active listening allows her to remain responsive to the unique challenges faced by families and children. To Merisotis, leaders like Albright represent the vanguard of the human work paradigm.

This description illuminates the essence of work that belongs uniquely to humans—work that cannot be replicated by AI. Empathy, compassion, moral discernment, and authentic communication are not algorithmic outputs; they are deeply human capacities. Equally important is the ability to synthesize complexity, to evaluate ambiguous situations, and to anticipate human behavior in ways that draw not only on logic but on wisdom born from lived experience. In this sense, human work is not simply about executing tasks but about exercising judgment and applying meaning to action.

Beyond skills and knowledge, human work connects us to purpose. It enables us to grow as individuals, to sustain ourselves materially, and to contribute to others through learning, earning, and service. It is this convergence—between personal fulfillment, social contribution, and the pursuit of meaning—that sets human work apart. Machines can be programmed to produce results, but they cannot generate purpose.

Consider the concept of service. Serving others is not merely a function but an expression of meaning. When people serve, they meet not only the needs of others but also their own need for purpose. Service provides the foundation for healthy communities and strengthens the bonds of society as a whole. It requires intentionality, commitment, and moral awareness. Machines cannot grasp this concept. They can simulate helpfulness but cannot experience what it means to give oneself in service to another.

Merisotis concludes that work has never been only about jobs. Rather, it has always been about the intersection of earning, learning, and serving. This triad forms the new paradigm of human work in an age increasingly shaped by intelligent machines. Each element is essential: earning provides the means to live, learning allows us to adapt and grow, and serving gives life meaning beyond ourselves. Without all three, the quality of our lives is diminished.

Seen this way, human work is not disappearing in the age of AI—it is being redefined. As machines take on more of the routine and technical tasks, the uniquely human dimensions of work—empathy, ethics, creativity, judgment, and service—become even more essential. Human work is not simply what remains once automation has taken its share; it is the work that matters most, the work that affirms our value as human beings.

Comments